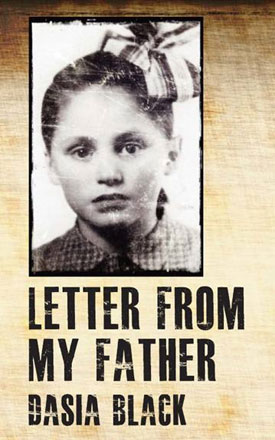

Dasia Black

Brandl & Schlesinger, 2012

The book would not have been written without my editor Diana Giese. She has been consistent in asking for more and better, in maintaining my courage when it flagged, in suggesting structural changes and showing remarkable sensitivity to what I wanted to say and what I chose to omit.

Dasia Black

READ REVIEWS

|

|

|

Dasia Black, Letter from my Father, extracts

‘For my tenth birthday, my new mother and father had a special dress made for me. How did they manage to get such lovely navy blue wool crepe material? Probably by bartering, since the fabric shops had nothing in their windows, the German mark being worth little until it was re-issued in 1950. I had a number of fittings because it was quite a complicated style. It was long-sleeved and had a semi-circular yoke with deep pleats falling from the centre. My parents must really love me, I thought, because they arranged for the edge of the yoke to be delicately embroidered with the most beautiful yellow and orange flowers with green buds. The dress had a white Peter Pan collar and a heart-shaped flower-embroidered pocket on each side.

It was the most beautiful dress I had ever seen. I couldn’t believe it was mine. I was very grateful that Mother and Father wanted me to have this special dress. They must have paid a lot of money for it. We had a professional photograph taken, with me in the centre and Father and Mother on each side. As in most photographs of the day, I had my arm around my mother, since somehow she did not find it natural or comfortable to put her arm around me. I had my hair done in the most flattering way: two plaits of hair laid across the top of my head, one on top of the other, and two plaits hanging down my back. Each plait was secured with a navy ribbon. In addition to the new dress, like most of my friends I also got a navy skirt and a shirt with a sailor collar. This was how “proper” European girls were dressed.

Then one day disaster struck. I was walking home with Ilonka after a party when we came across a puddle in the road. While she walked daintily around it, I decided to jump across. But it was too wide and I fell in. My dress, my beautiful dress with its embroidered flowers, was spattered with mud. How can I ever show my parents? I agonised. After discussing it with Ilonka, we decided to go home and try and clean it up. Fortunately my parents were out, so we locked ourselves in the bathroom, filled the tub with water and washed and washed and scrubbed and scrubbed. But the yellow and orange flowers just got duller.

My mother returned to find us still hard at work in the bathroom. We were made to open the door. She was scandalised. You naughty ungrateful child! she scolded. Why can’t you look where you’re going? All that scrubbing had just made things worse. The dress was somehow cleaned up, but it was never as beautiful again.

I was chastened. I knew I had to be much more careful in future, and do less jumping.’

(from New Parents)

‘The Centre for Family Research was housed in rooms that had been occupied in the 1930s by Ernest Rutherford and his team as they worked on radium, and the staff was still nervous about possible after-effects. The Director took me on a tour of this great University. We strolled on the lawn in front of King’s College, founded by Henry VI, past the library of Trinity College designed by Christopher Wren, and the college where Isaac Newton wrote his Principia Mathematica. It was intoxicating to feel the presence of these giants.

All was not historical grandeur, courtesy and scholarship. My lodgings were in a rundown B&B in a dilapidated old house, a tiny room up a flight of stairs smelling of musty carpets with a faint whiff of urine. The landlord was hairy, red-headed and rotund and always wore a singlet and baggy stained pants, no matter how cold it was. I survived the breakfasts in the dungeon-like dining room beneath the stairs by spending them with a charming Japanese lady scholar who was also visiting the University.

The evening meals were a challenge. My Australian dollar was worth half an English pound, but a simple pasta dish cost twenty pounds. I ate Indian and Italian food or went to the nearby pub and ordered whatever was on the board for the day. Nutritionally this must have been the worst period I had been through since the War.

A few days before the end of my stay, a pipe burst and flooded my room. I could no longer take the smell and the discomfort and accepted a friend’s offer to move into her tiny two-room digs at Emanuel College. What a relief! I enjoyed her youth and intellectual curiosity as well as the company at High Table at College dinners.

Back in Sydney I attended grandparents’ day at three-year-old Anna’s kindergarten, Jonathan and family having returned to Sydney after their American stint. It was a wonderful occasion. Then, for my birthday, my mother gave me a thoughtful gift. It was a certificate showing a many-branched tree heavy with leaves, a tree in full bloom. An inscription informed me that five trees had been planted in Israel in honour of my five young shoots: Zak, Nathan, Rachel, Adrian and Anna. This was one of those rare moments when I glimpsed my mother’s deep concern and love for me.

Simon and Jonathan urged me to shift the focus of my life from research and writing at my computer to getting out and looking for a new partner. Often I wished they would just leave me alone. I felt I had created a reasonably good life for myself and did not need a man. This was certainly true most of the time— but not always.

One morning I was in my car outside the townhouse scraping the old registration label off the windscreen with a sharp little knife— and not doing it well. My neighbour Henrika passed by and I called out in frustration: I need a man for this. I need a man in my life.

She observed me coolly, and then replied: You do not need a man. You need nail-polish remover.’

(from Seeking Adventure)

|